Seventy-two-hour hearings in Nevada are where courts arraign defendants who are still in jail three judicial days after their arrest. Also called the “initial appearance,” 72-hour hearings are also where defendants or their criminal defense lawyers can ask the judge to lower the bail amount or grant O.R. release.

Defendants who bail out before they can have a 72-hour hearing have their arraignment scheduled a few weeks later.

In this article, our Las Vegas criminal defense attorneys will address the following key issues regarding 72-hour hearings in Nevada:

- 1. Overview

- 2. Who Must Be There

- 3. Right to Attorney

- 4. Whether Family Can Attend

- 5. Timing

- 6. Who Gets 72-Hour Hearings

- 7. Bail Reductions

- 8. 72-Hour vs. 48-Hour Hearings

- 9. Preliminary Hearings

- 10. “Binding Over” to District Court

- Additional Reading

1. Overview

A 72-hour hearing is another word for arraignment or initial appearance. It is where defendants who are still in custody following their arrest get formally charged by a judge in open court. 72-hour hearings are a defendant’s first opportunity to see a judge in person (or through video-conferencing).

It is at the 72-hour hearing that prosecutors give defendants (or their defense attorney) the formal complaint listing the criminal charges they are accused of. The judge reads aloud the complaint (unless the defendant “waives” the reading). Prosecutors also hand over the discovery, which is a packet containing all the available evidence so far in the case such as police officer reports.

If the defendant is facing only misdemeanor charges, the defendant will enter an initial plea of not guilty. Then, the judge may schedule a trial, though the vast majority of cases are resolved through a plea bargain. If the defendant is charged with a felony, then the court will schedule a preliminary hearing. In-custody defendants have their preliminary two weeks later unless they agree to delay it.1

Can police hold you for 72 hours?

Yes, people can be detained for 72 hours following an arrest. However, if the District Attorney fails to bring formal charges by the 72-hour hearing, the suspect may be eligible for release.

Note that the 72 hours refer to business hours, which exclude holidays and weekends – called non-judicial days. This means some defendants may have to wait in jail for many days before their 72 hour hearing.

Delays in bringing formal charges often occur in drug cases when the prosecution is awaiting lab test results. In these situations, the judge has the discretion to decide whether to keep the suspect incarcerated until the D.A. is ready to file formal charges.2

2. Who Must Be There

Defendants must be at their 72-hour hearings. Note that sometimes defendants are video-conferenced in from jail.

72-hour hearings are usually the first time defendants see a judge in Nevada

3. Right To Attorney

Defendants’ criminal defense attorneys may appear along with the defendant at 72-hour hearings.

4. Whether Family Can Attend

Usually, a defendant’s family can attend the 72-hour hearing in the courtroom.

5. Timing

Seventy-two-hour hearings must occur within three (3) judicial days of a defendant’s arrest, unless the defendant is released first (for example, by posting bail).

Unlike calendar days, judicial days do not include weekends, holidays, or other days on which the justice court is closed. So a person arrested Friday night in Las Vegas on Memorial Day weekend does not get a 72-hour hearing until the following Thursday – the day after the 48-hour hearing.2

6. Who Gets 72-Hour Hearings

Only defendants who are still in custody three judicial days after their arrest. Defendants who get released on bail or O.R. (own recognizance) still get an arraignment, but it is often weeks or months later.3

7. Bail Reductions

Seventy-two-hour hearings may double as bail hearings, during which the defense attorney asks the judge to reduce or eliminate bail entirely (O.R. release). Note that if the judge refuses, the defendant can still request bail reductions at a later time.

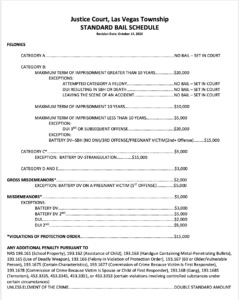

Also note that all Clark County courts have a bail schedule. This means that in most cases, bail is automatically set depending on the class of crime the defendant was arrested for. But judges have the discretion to change the amount at anytime.

Defendants typically ask for bail reductions or O.R. release at 72-hour hearings.

Sometimes judges choose to keep defendants in custody without the option to bail pending the resolution of the case. This typically occurs in murder cases or where the defendant is a public safety risk or flight risk. Judges also have the discretion to release defendants on house arrest with electronic monitoring pending trial.

Some factors that may increase a defendant’s chances of getting released on bail or granted O.R. include that the defendant:

- has strong community ties

- has family in town

- is gainfully employed

- does not pose a flight risk and surrenders his/her passport

- is facing charges for non-violent crimes

- owns no firearms

- has no prior criminal history

8. 72-Hour vs. 48-Hour Hearings

Forty-eight-hour hearings are not really hearings. They occur in the judge’s chambers, without the defendant, the defense attorney, or the prosecutors. (Sometimes defendants may appear by video-conference from the detention center, and sometimes the defense attorney is present.)

The purpose of 48-hour hearings is just to review whether sufficient probable cause exists to keep detaining the defendant until the 72-hour hearing. Judges can also use the 48-hour hearing to adjust bail, but they typically wait until the 72-hour hearing to make any changes.

In contrast, 72-hour-hearings occur in open court. Defendants, defense attorneys, and prosecutors may attend. At the 72-hour hearing, the defendant is formally charged. By the 48-hour hearing, charges are still only pending.4

9. Preliminary Hearings

A preliminary hearing is like a mini-trial in justice court, where both the defense and the prosecution can call witnesses and present evidence. The purpose of prelims is for the judge to determine whether there is still probable cause that the defendant is guilty.

If there is no probable cause, the judge will dismiss the case and release the defendant (if they are not already bailed out). If there is probable cause, the judge will set the case for an arraignment in district court. This is called bounding the case over to the district court.

Recall that prelims occur only in felony and gross misdemeanor cases.

10. “Binding Over” to District Court

When a defendant loses a preliminary hearing in justice court, the criminal case gets transferred (“bound over”) to district court. Once the case gets bound over, the case is set for an arraignment in district court. Then at the arraignment, the district court judge will set the case for trial.

Additional Reading

For more in-depth information, refer to these scholarly articles:

- Probable Cause, Probability, and Hindsight – Journal of Empirical Legal Studies

- Putting Probability Back into Probable Cause – Texas Law Review

- Probabilities in Probable Cause and Beyond: Statistical Versus Concrete Harms – Law and Contemporary Problems

- Probable Cause Pluralism – Yale Law Journal article on the complexities of the probable cause standard.

- Probable Cause Revisited – Stanford Law Review article discerning how probable cause operates.

Legal References

- See, for example, Meyer v. Balaam, (April 28, 2020) NV District Courts – Trial Orders Second Judicial District Court of Nevada, Washoe County, 2020 Nev. Dist. LEXIS 255. See also NRS 171.178. See also Huebner v. State, (1987) 103 Nev. 29, 731 P.2d 1330. See also Powell v. State, (1997) 113 Nev. 41, 930 P.2d 1123.

- See note 1. NRS 171.178.

- See NRS 1.130; Rules of the District Court of the State of Nevada, Rule 4. Nonjudicial days.

- See NRS 178.484; also see NRS 171.178; see NRS 174.015.