In Colorado, an indictment is a formal charge issued by a grand jury alleging that you committed a specific crime.

While most criminal cases in the state begin with a “complaint” or “information” filed directly by a prosecutor, indictments are reserved for more complex cases, such as organized crime, white-collar fraud, or first-degree murder.

A grand jury indictment serves the same purpose as a judge’s finding of probable cause: It moves the case from the investigation phase into the pretrial phase. Once indicted, you must appear in court to enter a plea and begin your defense.

Below I discuss what you need to know about indictments and the grand jury process in Colorado.

The Indictment Document

An indictment is a written statement presented by a grand jury to the district court, charging you with the commission of a Colorado crime.

Unlike a trial jury, which decides guilt or innocence, a grand jury’s sole job is to determine if there is probable cause to believe a crime was committed and that you committed it.

The document itself must describe the offense with “reasonable certainty,” including your name, the crime charged, and the time and place it occurred.1

Indictment vs. Information

Most Colorado criminal cases are charged via information or complaint, not indictment. The practical result—being charged with a crime—is the same, but the path to get there differs.

When prosecutors file a “direct information,” they make the decision themselves. To help ensure the charges are valid, the court then schedules a preliminary hearing where the judge (not a jury) listens to the evidence and decides if there is probable cause to proceed to trial. Your defense attorney can be present and can cross-examine witnesses.

When prosecutors use a grand jury, the process is secret and one-sided (“ex parte”). Your defense attorney is generally not allowed in the room, and you have no right to cross-examine witnesses. Since the grand jury determines whether there is probable cause you committed a crime, there is no need for you to have a preliminary hearing.2

From what I have seen, prosecutors often prefer indictments in three situations:

- Complex cases: When the charges include racketeering (COCCA) or securities fraud, a grand jury’s subpoena power helps gather documents.

- Witness protection: In gang-related or sensitive cases, keeping the witnesses’ identities secret until trial is crucial.

- Political cover: In high-profile officer-involved shootings, a prosecutor may use a grand jury to avoid the appearance of bias.

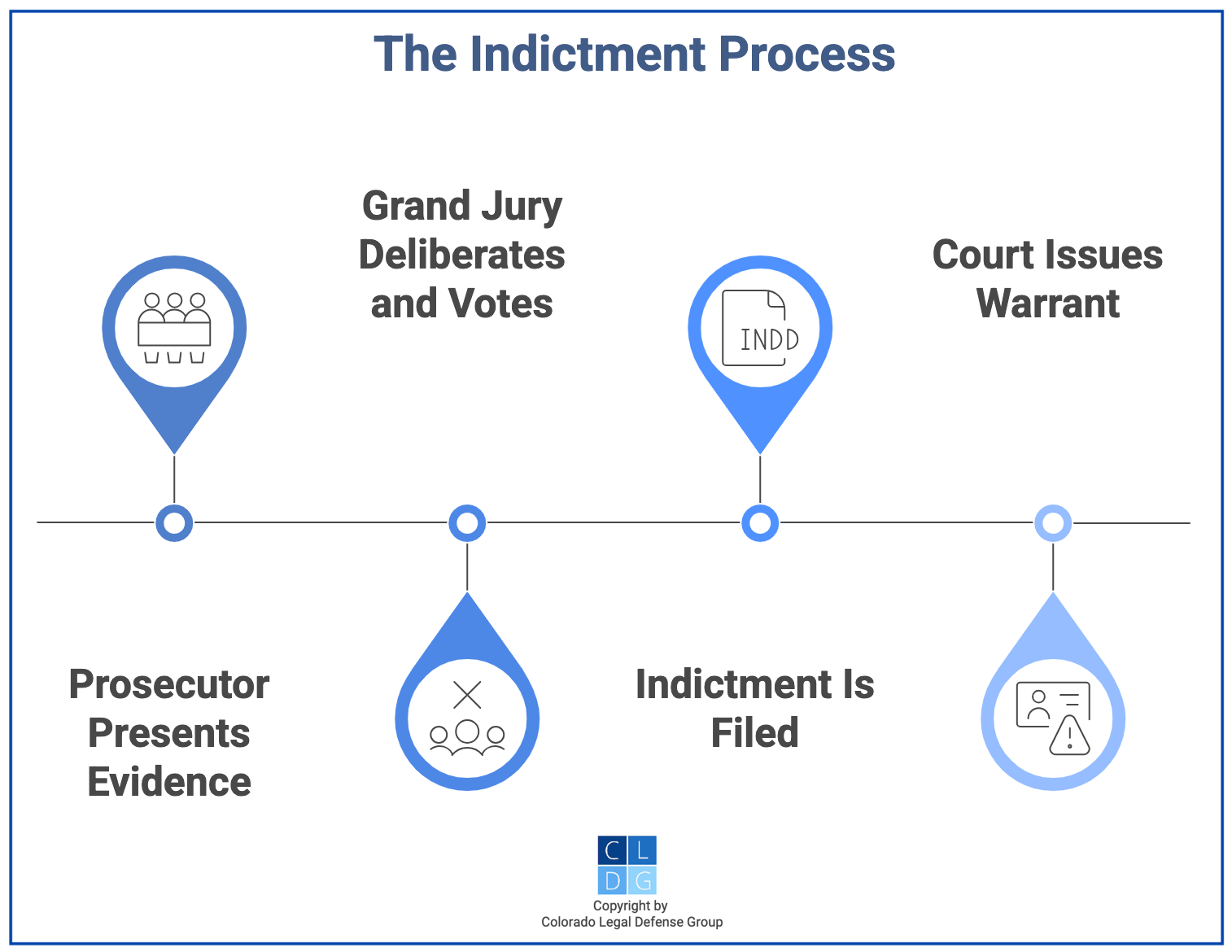

The Grand Jury Process

A grand jury consists of 12 or 23 members selected from the community. In Colorado, state-level grand juries (investigating multi-district crimes) consist of jurors from various counties.

Grand jury proceedings are secret. Colorado law mandates that “no person may disclose the existence of the indictment” until you are in custody or on bail.3 The Colorado Supreme Court has emphasized that this secrecy is vital to encourage witnesses to come forward and to prevent suspects from fleeing.4

The prosecutor presents witnesses and physical evidence to the jurors. The standard of proof is probable cause, which is much lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used at trial. Probable cause exists if the evidence is sufficient to induce a person of ordinary prudence to reasonably believe you committed the crime.

- If the jury has 12 members, at least 9 must agree to indict.

- If the jury has 23 members, at least 12 must agree to indict.

If the required number of jurors agree, they return a “true bill,” effectively charging you.

Defendants and their attorneys are not present during grand jury proceedings.

Challenging an Indictment

Even though you and your defense attorney are not present during the grand jury proceedings, you can still challenge the validity of the indictment after it is issued.

For instance, your attorney can file a motion to dismiss for lack of probable cause. This asks the district court to review the grand jury record (“transcript”) to check that the evidence presented actually supported a finding of probable cause. When examining the record, the court must review the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution.

Your attorney can also challenge an indictment if the prosecutor engaged in misconduct that “substantially influenced” the grand jury’s decision. This might include:

- Failing to present highly exculpatory evidence (evidence that indicates your innocence),

- Improperly pressuring the jurors, and/or

- Violating the secrecy of the proceedings.6

After the Indictment

Once the “true bill” is returned, the following steps occur:

- Warrant or Summons: The court issues a warrant for your arrest or a summons ordering you to appear in court.

- Unsealing: The indictment is unsealed and becomes a public record once you are in custody.

- Advisement: You appear before a judge to be formally advised of the charges.

- Arraignment: You enter a plea of guilty or not guilty.

Interestingly, if a prosecutor tries to file charges via “information” and a judge dismisses them for lack of evidence at a preliminary hearing, the prosecutor can still go to a grand jury to seek an indictment for the same crime. In effect, the grand jury route gives the district attorney or Attorney General a “second bite at the apple.”7

Once you are charged, whether by indictment or information, the case proceeds into the pretrial phase. The majority of cases resolve through a plea bargain, often well before the preliminary hearing. Otherwise, the case eventually goes to trial.

The vast majority of cases begin with an information rather than an indictment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is an indictment a conviction?

No. An indictment is merely a formal accusation. It is the charging document that starts the felony trial process. The prosecutor must still prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt at trial to get a conviction.

Can I testify before the grand jury if I am the target?

You have the right to request to testify, but the grand jury is not required to let you. If they do allow it, you must waive your right against self-incrimination, meaning anything you say can be used against you. It is rarely strategic for a suspect to testify.

Why do prosecutors use grand juries instead of preliminary hearings?

Grand juries are used when the investigation requires subpoena power to get bank records or force witnesses to talk. They are also used to keep the investigation secret so suspects do not destroy evidence or flee before they are charged.

What is a “No Bill”?

If the grand jury votes against indicting (fewer than 9 jurors vote for it), it is called a “No Bill.” This usually ends the case, although the prosecutor could theoretically try again with new evidence.

Additional Resources

For more in-depth information, refer to these scholarly articles:

- Restoring the Grand Jury – Fordham Law Review.

- Eliminate the Grand Jury – Criminal Law & Criminology.

- The Early History of the Grand Jury and the Canon Law – University of Chicago Law Review.

- Demythologizing the Historic Role of the Grand Jury – American Criminal Law Review.

- The Useful, Dangerous Fiction of Grand Jury Independence – American Criminal Law Review.

Legal References

- C.R.S. 16-5-204. C.R.S. 16-5-201.

- People v. Thompson (Colo. 2008) 181 P.3d 1143 (discussing the investigatory and protective nature of the grand jury). See also People v. Gregg (2025) 576 P.3d 725 (holding that if an indictment or information includes habitual criminal counts, the defendant now has a constitutional right to have a jury, rather than a judge, determine if the prior crimes were “separate and distinct” episodes).

- C.R.S. 16-5-205.5.

- See note 2.

- People v. Luttrell (Colo. 1981) 636 P.2d 712.

- Same. C.R.S. 16-5-204.

- People v. Noline (Colo. 1996) 917 P.2d 1256.